Dear Nervous system, what are you doing?

I bounced from one nervously anxious state to another, glimmers of joy looped through paralysing dissociation, raging anger and complete exhaustion. My nerves were shot. A toxic environment, caused by another human, had me thinking that I was going crazy! It turns out my nervous system was keeping me safe. Safe in the face of unfathomable volatility, unpredictable hostility and cruelty disguised as malevolent kindness.

Our nervous system boasts an innate ability to adapt to our ever-changing needs. Whether we're out for a brisk jog, honing our skills in sports training, engaged in a state of flow at work, revelling in the warmth of love, or dancing with friends, each of these activities demands energy and vitality from our bodies to perform optimally.

Conversely, our bodies possess the capacity to transition into states of low energy; we instinctively know how to unwind and drift into meditative and tranquil states between wakefulness and sleep, allowing for ample rest, which is necessary for adequate digestion, cellular repair, and rejuvenation.

The term "orthostatic" derives from the Greek words "orthos," meaning upright, and "histanai," meaning to stand; this postural shift prompts a series of adjustments within the cardiovascular system to safeguard optimal blood flow to the brain and prevent a sudden decline in blood pressure. Our nervous system handles this orthostatic challenge, orchestrating adaptations across the cardiovascular, respiratory, musculoskeletal, and hormonal systems, fine-tuning our physiological responses to the demands of daily life, all without conscious awareness.

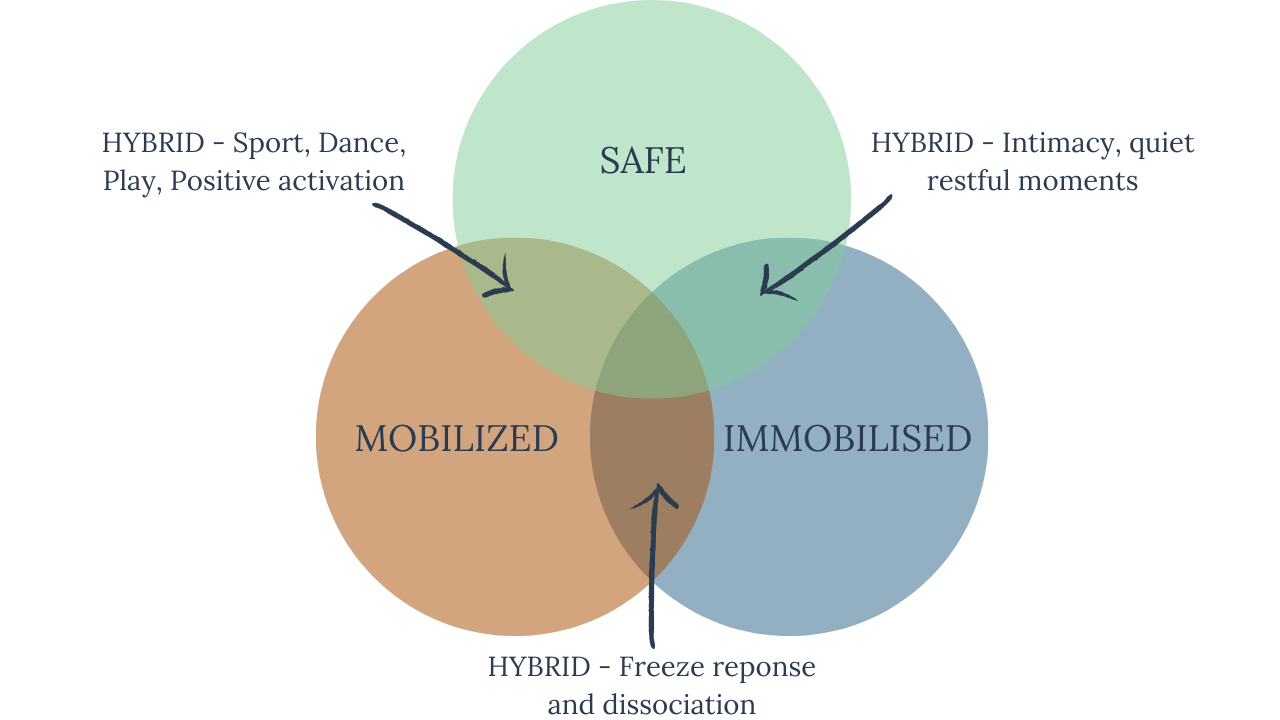

The stress response serves as a vital mechanism to shield us from both perceived and genuine threats. However, the brain can sometimes become conditioned to perceive threats from past experiences, activating responses in the here and now, often known as "triggers". These triggers or activation responses are based in the nervous system; into heightened or diminished energy states—adaptive stress responses, as depicted below. While this heightened state can offer protection in the face of immediate danger, remaining in these states for extended durations proves less beneficial.

A conceptual framework derived from polyvagal theory, developed by Dr Stephen Porges, helps us to understand the hierarchical organisation of the autonomic nervous system's responses to stress and social engagement. The ladder metaphor represents a continuum of physiological and behavioural states that individuals may experience in response to perceived threats or safety cues, ranging from states of safety and connection to states of defence and disconnection.

The polyvagal ladder emphasises that our physiological and emotional responses to stress are not binary but rather exist along a continuum. Depending on the perceived level of safety or threat in our environment, we may move up or down the ladder, shifting between states of social engagement, mobilisation, or immobilisation.

As we move into stress adaptation in the face of THREAT, the "fight or flight" response kicks in. However, if fighting or fleeing does not serve to keep us safe, another two stress responses take over: "freeze or flop"

Polyvagal theory offers valuable insights into the physiological and psychological mechanisms underlying anxiety and depression. By understanding how the autonomic nervous system responds to stress and social interactions, we can gain a deeper understanding of these mental health conditions and develop more effective interventions.

-

Dysregulation of the Autonomic Nervous System: Anxiety and depression are often associated with dysregulation of the autonomic nervous system, particularly the sympathetic and parasympathetic branches. Individuals with anxiety disorders may exhibit heightened sympathetic arousal, leading to symptoms such as increased heart rate, rapid breathing, and muscle tension. Conversely, depression may be characterised by reduced sympathetic arousal and impaired parasympathetic function, resulting in lethargy, fatigue, and emotional numbness.

-

Vagal Tone and Emotional Regulation: Polyvagal theory emphasises the role of vagal tone—the functioning of the vagus nerve—in regulating emotional responses and stress resilience. Low vagal tone has been associated with increased susceptibility to stress, anxiety, and depression, as it may impair the individual's ability to regulate emotions and cope effectively with challenges. Conversely, high vagal tone is linked to better emotional regulation, social engagement, and overall well-being.

-

Social Engagement and Social Support: The ventral vagal complex, a key component of the polyvagal system, is involved in promoting social engagement and connection. Deficits in social engagement can contribute to feelings of loneliness, isolation, and depression. Individuals with anxiety disorders may also experience social difficulties and avoidance behaviour, further exacerbating their symptoms. Enhancing social support and fostering positive social interactions can help regulate the autonomic nervous system and alleviate symptoms of anxiety and depression.

-

Trauma and Dysregulation: Traumatic experiences can impact the functioning of the autonomic nervous system, leading to dysregulation of physiological and emotional responses. Polyvagal theory suggests that traumatic stress can disrupt the normal hierarchy of autonomic responses, resulting in hyperarousal, hypoarousal, or a combination of both. The dysregulation responses may contribute to the development and maintenance of anxiety and depression symptoms.

If you have complex PTSD, it becomes increasingly difficult to regulate the nervous system into a place of safety, causing many knock-on effects – difficult moderating finances, relationships, workload, physical health, emotional health, behaviours, anxiety, etc.

These can be addressed through trauma-based therapeutic mind-body interventions aimed at regulating the autonomic nervous system and promoting emotional well-being. Practices such as mindfulness, yoga, deep breathing, and biofeedback can help modulate vagal tone, enhance emotional regulation, and reduce symptoms of anxiety and depression. Other beneficial forms of therapy can include yoga therapy, somatic therapy, dance therapy, art therapy, EMDR, emotional freedom technique and some elements of CBT.

References:

Dana, D (2020) Befriending Your Nervous System: Looking Through the Lens of Polyvagal Theory Audible Audiobook – Original recording Deborah Dana LCSW (Author, Narrator), Sounds True (Publisher)

Porges, S.W. (2011) The Polyvagal Theory: Neurophysiological foundations of emotions, attachment, communication, and self-regulation. New York: W.W. Norton.

Schwartz, A. (2016) The complex PTSD workbook: A mind-body approach to regaining emotional control and becoming whole. Berkeley, CA: Althea Press.